In part one, we focused on things that a player can do to up their game with respect to a practice regimen. Part two is also going to focus on the practice element, only this time we are looking at the practice of good music reading. It doesn’t matter whether you started reading music from an early age or if you’ve never really read music before; you can always get better at it.

Reading music is an often overlooked part of the music business for most players. While certainly those with a good ear can often get away with not reading, the ability to read music–and do it well–puts the musician in a category of players way above average, even if their ability is not as advanced as others. Put simply, the ability to read music will often get you the gig over better players that can only use their ears. You’d be surprised how many classical players don’t have the most killer chops, but are in high demand for many different musical ensembles due to their great reading abilities.

So how does one get better at reading music or even get started? Most music teachers will point the student the way to the Mel Bay book (of music reading) and say “start here”. This is not bad advice. I think that before anyone begins to read music, they first need to understand and familiarize themselves with the landscape of a music chart. This includes several things: 1) the notes themselves, 2) the note values & relationships, 3) time & key signatures, 4) chart markers/directors and 5) accidentals & ornaments. A book like the Mel Bay book will cover all of these in detail, so it is important to have a basic understanding of music notation before moving any further. For the purpose of this discussion, we’re going to assume that the reader already has a rudimentary understanding of what the numbered points above mean.

Now, if you are a total newbie it is important to recognize the challenge of rhythms. Even with a proper understanding of musical notes and where they fall on the staff, it is the combination of the rhythmic interplay that can make chart reading very difficult. This includes not only the note values themselves, but the rest values. As such, make sure to start with very simple concepts as charts. For example, songs/charts that have a lot of longer valued notes and/or rests–at least quarter notes, but also half and whole notes. Look for 4/4 time signatures, slower BPM’s and avoid charts with too much black ink!

In the beginning, the reader will have to count as they play through a chart. Charts that are uniform and symmetrical will be easiest to maneuver, for example charts with an even number or round number of bars (i.e. 16, 24, 32, etc.) Look for charts with as few notes as possible and as few accidentals. A tip here is to find songs in the key of C or Am, where all the notes will be natural notes. Accidentals, along with more complicated rhythms can definitely trip the reader up, at least in the beginning. A couple examples of these types of easy songs are things like “Jingle Bells” or “When the Saints Go Marching”.

The reason it is key to start simple is that in reality (at least) three different things are happening as one reads music. The first is actually “reading” the musical note–is it a C or an F, etc? The second is the combination of the musical note and the rhythm. For example, play an F for 2 beats. Remember that music isn’t just all notes–it is the space in between. As such, the reader needs to know not only how long to play a specific note, but when to stop playing it and perhaps rest for a beat. This can get really, really complicated, very fast. Finally, the reader has to find that note on their instrument and start to get comfortable with the relationship of reading a note at the same time they are fingering it on their axe. This is all much more complicated at first than it sounds, but it will get easier over time as the player reads more and more.

Once you have mastered the simpler, natural scales it is time to move into accidental territory. A couple keys to start with are “F” and “Bb”. F has one flat in its major scale and Bb has two flats. The scale and/or key note will generally be determined by how the staff looks prior to the time signature on the far left of the chart at the top. For example, the key of Bb will show a “b” (flat) on the staff lines for B and E. Remember, that unless the notes on these staff lines are further altered with accidentals (in the measures of the song) they will always represent the flatted (or sharped) note when you play them.

Keep in mind that, although an easy major scale may not have more than one or two flats, it is possible for the composition to have accidentals on other notes. Jazz does this A LOT. Remember that for each bar that a note has an accidental, that note will stay the same value through the entire measure, unless it is changed into something else via accidental. So for example, if you see a note that is flatted in a 4 beat measure, the repeats of the notes (in that measure) will not carry a flat, because the assumption is that you understand that they are also played as “flats”. This is unless the note is changed in that same measure, from which it will take on the changed value for the rest of the measure. The natural key note (meaning the correct note according to the key and staff) will resume in the next measure.

One last thing to consider with respect to note values and rhythms is how the individual notes are related to each other. This is generally notated as “tie lines” or other odd symbols that either group together a few notes at a time or are notated in between two notes. For example, two quarter notes “tied” together will sound out for the length of a half note. When the note is tied, but changes value it is known as a “slur”. On guitar, this is often played sliding from one note to another, without distinguishing the notes in between, whereas a “glissando” will hear each of the notes between the start and end of the slur. Notes are also often tied together via a “tuplet” (e.g. triplet, quintuplet, etc.), where the notes themselves are played together over a group of beats. An example here is a triplet, which generally plays three notes (with the correct corresponding rhythm) over two beats. The last common note relationship is the notation of a “chord” which shows all of the notes (of the chord) on top of each other in the chart, signifying to play them all at the same time, as you would a chord.

Once you have mastered the easier scales and rhythms, it is now time to move to the next level. One tip that can help a lot with rhythmic notation (in the beginning) is to ditch the instrument for a minute and just clap the rhythms. Something like a Mel Bay book or other beginning music reading literature will help define common rhythms so that you can familiarize yourself with how they feel before seeing them in a chart for the first time. I want to stress that, at least at first, rhythmic notation can feel extremely complicated and overwhelming. Again, start simple before moving on to harder stuff. This can take a while to develop, so take your time and have A LOT of patience. For guitarists, a Scott Henderson head (or piano, Robert Glasper) will seem like a foreign language if you don’t master the basics first.

There are many other musical notations in a chart in addition to the notes/rhythms represented on the staff. While certainly knowing the correct notes and rhythms is half the battle, the musician is not done here. Often charts have other markers, the most common being dynamics, articulations, ornaments and directions, that are key to the understanding of HOW to play the chart. This means in general, the action of the notes/rhythms–how they are played, at what volume, etc. AND where your eyes need to go when reading the chart.

The first three markers generally tell the musician how to play the note or phrase. Dynamics relate to how loud or soft the notes are played and whether the volume of the notes increases or decreases as the phrase is played. Dynamics range from Pianissimo (very soft) to Fortississimo (very loud) with the accompanying crescendo or decrescendo advising on whether to get louder or softer as you play. Articulations specify the length, volume and style of attack. These are commonly referred to as “accents” and have their specific Italian names as well. Ornaments are notations that modify the pitch pattern of a specific note. “Trills” (rapidly playing two notes back and forth) or “Tremolos” (rapidly playing a single pitch) are very common examples of ornaments.

The direction markers are a little different than the above notations. Direction markers are like road signs telling the musician where to drive along the chart. Most musicians are likely familiar with a simple direction “:”, the repeat sign. This will appear at the end of a series of bars and signify the need to go back to the the first “:” sign and repeat the number of measures. Similarly, “simile” signs will instruct the reader to repeat a chord or section for a specific number of measures.

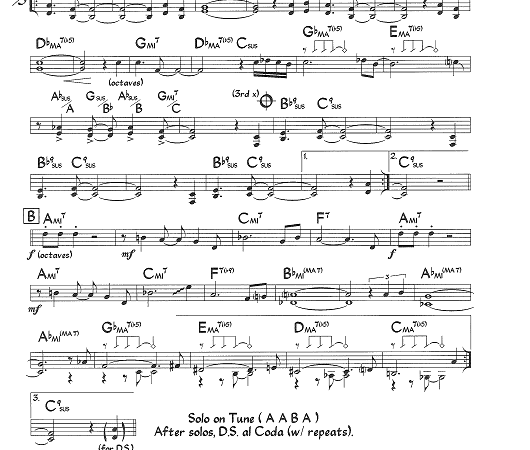

Often direction markers help to simply a chart in length, so it is not 40 pages long! Segnos, codas and brackets are employed to direct the reader to another part of the chart and/or to let the reader know when to move to a different part of the chart when they get done playing a specific part. A D.S. sign (simliar to %, but looks like an S on an angle with a line through it and two dots on either side) specifies a place in the chart where the reader will be directed back to upon seeing the phrase “D.S.” and then “al coda/fine/capo”. If the word “coda” is used, the reader will go back to the place in the chart where the “Segno” is and then play to the coda, which will move them to another part on the chart where another coda is. If the word “fine” is used instead, the reader will play from the Segno to where the chart says FINE and just end. The word “capo” signifies going back to the top of the chart and playing it all the way through. Brackets typically signify a first and second ending, which will often direct a reader to a different section of the chart when playing a specific section again. These will be numbered at the end of a section as 1. and 2., or even 3. and 4. or more.

With regard to chart directions, don’t forget about these. They are often overlooked and make a big difference in how one reads a chart. Additionally, as a chart writer these guys are your friends! They make it so much simpler to notate a chart in the least amount of space possible. This keeps the reader from having to constantly flip the pages of a chart while reading at the same time. I’ll tell you that between the chart itself, the wind, the ensemble and everything else, the less pages of a chart the better!

Now that the musician is familiar with chart notation, it’s time to look at and play some charts. My advice here is to play a chart that also has a recording along with it. The recording will act as training wheels and one can simply listen to the song and read the chart first to get an understanding of how the chart flows before playing along. I also prefer to listen to a recording and read the chart first (before playing along) to find where potential directions might lead to so as not to overlook them.

If you already have somewhat of a grasp on basic chart reading, go ahead and pull out a Real Book or even a Fake Book of standards that you know and get started. Like all practice, music reading should be employed as a regular task. Perhaps on one of the practice days, the mission is to practice reading a chart. The cool thing about integrating music charts into guitar practice is that you not only help yourself to learn the art of music reading, but you also learn new songs! AND, one doesn’t have to crowd up the RAM space in their brain because the chart is always available to be read again–and this time you’re already familiar with it, right?

A final note. As the reader begins to undertake the journey of music reading, take heed. This is not going to be an easy thing and may frustrate the practice session. Don’t wear yourself out. Take your time and take it slow. Even if all you do is learn 16 bars of a jazz standard at a time, take the time to learn it correctly while training your ears, mind and fingers to coordinate effectively. The more one practices music reading, the more familiar it will become. First, the notes will start to immediately sound in your head; then the fingers on your fret board will automatically move to those notes. Finally, as the rhythms become more and more familiar, your fingers will move from note to note without even thinking about it. This is when a music chart is properly “read” for the first time and is a fantastic experience. Like anything though, it takes time and practice. So go for it!

Comments are closed.